International Children’s Book Day (ICBD) is observed annually on 2 April, the anniversary of the birth of Hans Christian Andersen

The idea of an annual celebation of the day came from IBBY (International Board on Books for Young People). Each year a different National Section of IBBY sponsors ICBD. The sponsoring National Section suggests a motto for ICBD, and a message to the children of the world is written by a suitable person such as an internationally-known children’s author. The sponsoring National Section is also responsible for producing an attractive poster to promote ICBD. In addition, the sponsors encourage national celebrations of the day, such as activities in libraries and schools, special publications, book-related events, and media publicity.

International Children's Book Day 2007

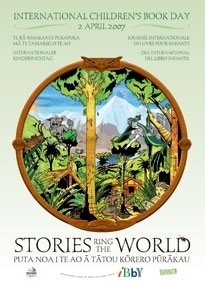

Storylines, in its role as the New Zealand Section of IBBY, was the sponsor for International Children’s Book Day on 2 April 2007. This involved design and production of an ICBD A1-sized poster superbly illustrated by Zac Waipara. The motto chosen was ‘Stories Ring the World’, and the accompanying message was written by New Zealand writer and Hans Christian Andersen Medal winner Margaret Mahy.

About the 2007 International Children’s Book Day poster - Zak Waipara

A circular frame provides a window onto the unique New Zealand landscape, illustrating the motto Stories Ring the World.

Ranginui and Papatūānuku (sky-father and earth-mother) are represented as carved figures embracing a world alive with the rich traditions of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Mountains, the sun, and moon are personified, legendary monsters prowl the forests, and the human element is depicted as part of this natural world, not separate from it.

The central tree symbolises Tāne Mahuta, God of the forest, who created the world of light by separating his parents Ranginui and Papatūānuku; planting his shoulders to the earth and pushing up the sky with his feet like a powerful tree. Kōpūwai, the giant dog-headed monster, rises above the horizon, while in the foreground Hatupatu runs past whare whakairo (traditional carved houses), pursued by Kurangaituku, the bird-woman.

A patupaiarehe (sprite child) and his friend the tuatara peer out from one side of the frame. On the other side another ancient survivor looks down on a tiny creature grovelling in the undergrowth: Gollum from The Lord of the Rings, the story that has recently made the New Zealand landscape known worldwide through Peter Jackson’s film version.

Below the frame a beetle crawls on the letter ‘D’, one of Margaret Mahy’s ‘black beetles’ – her first impression of text creeping across the page, before she learnt to read.

A message to the children of the world from Margaret Mahy of New Zealand

The 2007 sponsor was Storylines IBBY NZ Section and the message was by Margaret Mahy:

“I will never forget learning to read. Back when I was really small, words scurried past my eyes like little black beetles trying to get away from me. But I was too clever for them. I learned to recognise them no matter how fast they ran. And at last – at last I was able to open books and understand what was written there. I was able to read stories and jokes and poems all by myself.

“Mind you, there were some surprises. Reading gave me power over stories, but, in a way, it also gave stories power over me. I have never been able to get away from them. That is part of the mystery of reading.

“You open the book, take in the words and the good story explodes inside you. Those black beetles running in straight lines across the white page turn first into words you can understand, and then into magical images and events. Though certain stories seem to have nothing to do with real life… though they melt into surprises of all kinds, and stretch possibility this way and that as if it were a rubber band, in the end good stories bring us back to ourselves. They are made up of words, and all human beings are anxious to have adventures with words.

“Most of us begin as listeners. When we are babies our mothers and fathers play with us, reciting rhymes, touching our toes, (This little pig went to market) or clapping our hands, (Pat-a-cake! Pat-a-cake). Games with words are spoken aloud and, as very small children, we listen and laugh at them. Later, we learn to read that black print on the flat page, and, even when we read in silence, a certain voice is there too. Whose voice is it? It might be your own voice – the reader’s voice, but it is more than that. It is the voice of story, speaking from inside the reader’s head.

“Of course there are many ways in which stories are told these days. Films and television have tales to tell, but they do not use language in the way books do. Authors who work on television or film scripts are often told to cut back on the words. ‘Let the pictures tell the story,’ say the experts. We watch television with other people, but when we read we mostly read alone.

“We live in a time when the world is crowded with books. It is part of the reader’s journey to search through them by reading and then reading again. It is part of the reader’s adventure to find in that wild jungle of print some story that will leap up like a magician… some story that is so exciting and mysterious that the reader is changed by it. I think every reader lives for the moment when the everyday world shifts a little, giving way to some new joke, some new idea, some new possibility given a truth of its own by the power of words. ‘Yes, that is true!’ cries that voice inside us. ‘I recognise you!’ Isn’t reading exciting!

Te rā whakanui pukapuka mā te tamariki o te ao, 2007

E kore rawa e warewaretia e au taku ako ki te pānui.

I te wā e tino pakupaku tonu ana au, ka takawhiti mai ngā kupu i mua i ōku karu, pēnā i te pītara pango iti e whakamātau nei ki te oma atu i a au.

Engari, he mātau rawa au mō aua kupu rā. I ako au i ngā kupu rā kia tino mōhio au ki ō rātou āhua ahakoa pēhea te tere o tā rātou oma. Nāwai rā, ā, ka tae rawa ake te wā i taea e au te whakatuwhera pukapuka, ā, i mārama anō au ki ngā kōrero i tuhia.

I taea e au te pānui i te pūrākau, te kōrero paki me te rotarota, ko au anake. Heoi anō, i puta mai hoki ētahi āhuatanga kāhore i whakaarotia e au. Nā te mōhio ki te pānui ko au te rangatira o ngā kōrero i pānuitia, engari, i ētahi wā anō, i riro kē au i te hā o ngā kōrero i pānuitia. Kua kore rawa e taea e au te whakarere i te pukapuka. Koia rā tētahi o ngā mea mīharo o tēnei mea te pānui.

Ka whakatuwhera koe i te pukapuka, ka pānui i ngā kupu, ā, ka pahū mai te kōrero rawe i roto tonu i a koe. Ko aua pītara pango anō rā ka oma tika tonu ra, whiti atu i te whārangi mā, ā, ka huri tuatahitia hei kupu e mārama ana ki a koe, kātahi ka hurihia hei ataata mīharo, hei tūāhua mīharo anō hoki. Ahakoa te āhua o te kore hāngai o ētahi kōrero ki te oranga tūturu o te tāngata … ko tā te kōrero pai he whakaohorere, he kukume pçnei, pēnā rānei i te tūponotanga ānō nei he hererapa te tūponotanga, heoi, i te mutunga iho, ko tā te kōrero pai he whakahoki i a tātou ki a tātou anō. Hangaia ai te kōrero i te kupu, ā, ko ngā tāngata katoa e hiahia ana ki te pāhekoheko tahi ki ngā kupu.

Tīmata ai te nuinga o tātou hei kaiwhakarongo. I a tātou e pēpi tonu ana, pāhekoheko tahi ai ō tātou māmā, me ō tātou pāpā ki a tātou, ka taki ruriruri rātou, ka whakapā i ō tātou matimati, (I haere atu tēnei kuao poaka ki te mākete), ka pakipaki rānei i ō tātou ringaringa. (Pat-a-cake! Pat-a-cake!). Ka whakahuatia ētahi kēmu kupu, ā, i a tātou e pakupaku ana, ka whakarongo, ka katakata hoki tātou ki ēnā. Nāwai rā, ka ako tātou ki te pānui i ngā kupu pango i runga i te whārangi paparahi, ā, i ngā wā ka pānui ā karu tātou i aua kupu kei reira tonu tētahi reo. Nō wai taua reo? Tēnā pea, nōu kē te reo – arā, te reo o te kaipānui, engari he mea anō kei tua atu. Koia rā te reo o te kōrero, e kōrero ana mai i roto tonu i te hinengaro o te kaipānui.

Heoi anō, he nui tonu ngā huarahi hei whakaatu i te kōrero i ēnei rā. Whakaatu ai te kiriata me te pouaka whakaata i te kōrero, otirā, he rerekē tā rāua whakamahinga i te reo i tā te pukapuka whakamahinga. Ko ngā kaituhi ka tuhi i te tuhinga pouaka whakaata, i te tuhinga kiriata rānei ka whakahaua auautia ki te whakapoto i te nui o ngā kupu. ‘Waiho, mā ngā pikitia te kōrero e whakaatu,’ te kī a ngā tohunga. Mātakitaki ai tātou i te pouaka whakaata i te taha o çtahi atu, heoi, ina pānui tātou, ka pānui takitahi kē tātou i te nuinga o te wā.

Noho ai tātou i tētahi wā, e puhake ana te ao i te pukapuka. Ko tā te kaipānui he whiriwhiri pukapuka mā te pānui me te pānui anō. Ko te mātātoa a te kaipānui he kimi i roto i te ngahere tuhinga i tētahi kōrero ka tarapeke ki runga pērā i te kaitūmatarau… i tētahi kōrero tino tōiriiri, tino mīharo hoki, e whakaawetia ai te kaipānui. Ki ōku whakaaro, tatari ai ia kaituhi mō te wā ka whakarerekētia te āhua o te ao o nāianei i te mana o te kupu, e puta mai ai tētahi paki hou, tētahi whakaaro hou, te tūponotanga rānei o tētahi huarahi hou. “Āe, e pono ana!” te tangi o te reo kei roto i tēnā, i tēnā o tātou. ‘E mātau ana au ki a koe!’ Kātahi te mahi tōiriiri ko te pānui!

In association with Reed Publishing, Storylines also produced Out of the Deep, an anthology of Māori, Pacific Island and Pākeha stories for children – stories that reflect the primary cultures within New Zealand. This anthology was edited by Tessa Duder and Lorraine Orman, and illustrated by Bruce Potter.